After living in Finland for seven years and hearing the same talks about internationalisation I have gotten an impression that Finland simply doesn’t know how to be international, how to measure it and how to benefit from it.

“We need to boldly tell people what a great place Finland is and make Finland the best place to study in the world”, Yle quoted Peter Vesterbacka, a former Angry Birds marketer and strong proponent of Finnish education.

He also noted that the potential money that huge numbers of foreign students could pay in study fees and living expenses would surpass the costs of running Finland’s institutes of higher education every year.

Wait. Does he mean that Finland’s institutes should be financed by foreign students? Is money the only benefit that internationalisation can bring?

Another question is whether current measures taken are enough to make Finland “the best place to study”. Let’s look at the numbers.

International students in Finland and the rest of the world

First, let’s look at the number of international student enrollment.

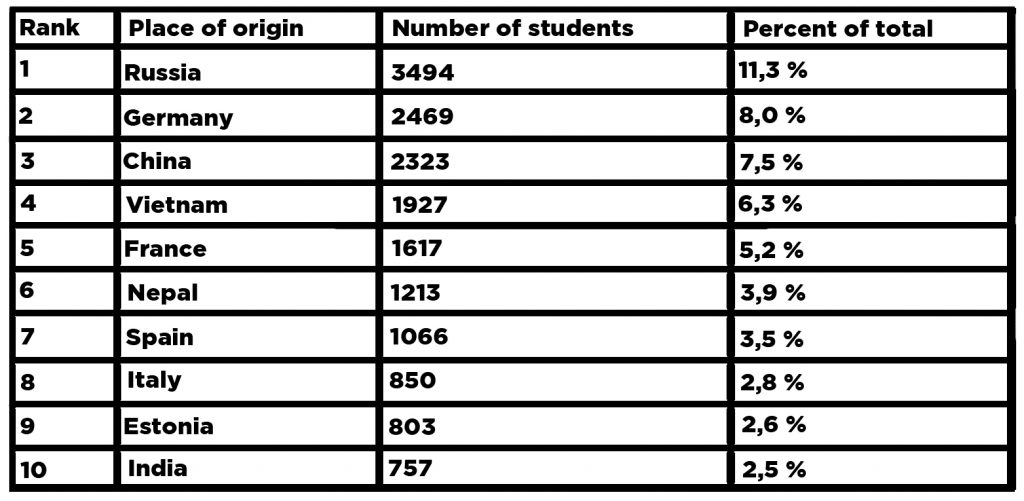

According to Centre for International Mobility (CIMO), there were 30,827 foreigners enrolled in Finnish higher education institutions in 2015. In 2007 the number was 19,718, so Finland has gained around 10,000 more students in the period of eight years. However, the number of international applicants has reduced by almost a third in 2015 compared to the year before.

Here are the top 10 countries with highest international student enrollment in 2015.

Source: The Centre for International Mobility (CIMO)

Just a few observations: In total, 76 percent of international students in Finnish universities came from outside of the EU/EEA countries in 2015. If they had to pay the tuition fees of 10 000 euros in average, that would make approximately 234 million euros a year. The total university state budget for 2016 is 585,5 million euros. So, basically in order to cover it Finland needs around 60 000 students outside of the EU. If the numbers continue to grow with the same speed probably in 30 years time it could be reachable. However, will these students be able or willing to pay the tuition fees?

It is also important to note that African countries and Sweden have disappeared from the top 10. The number of Swedish students have never exceeded 700 in general and is declining even though there are degrees available in Swedish. The number of Estonian students has been steadily at 800 students enrolled a year. It’s only Russia among all other neighbouring countries that keeps the numbers growing. Back in 2012 it overcame China and since then the number of students have been constantly increasing.

So, wouldn’t you bet on Russia instead of China in your marketing activities? However, there are more numbers to look at.

“Finland is among the minority of OECD countries suffering from a brain drain”, stated Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland in Strategy for the Internationalisation of Higher Education Institutions in Finland 2009-2015. This famous report recognized that the “low level of internationalisation is still one of the key weaknesses of the Finnish higher education and research system when compared with Finland’s competitors”. It is pretty well-reflected in the universities core funding structure, where international programmes and research hardly receive more than 3 percent at the maximum including Finnish students and researchers mobility.

I will conclude my numeric part of the article with the final portion of statistics provided by the World University Rankings – what are the World’s most international universities 2017? Finland has not made it into top 150 in which Russia is at 104. place.

“A striking feature of the upper reaches of the 150-institution table is the prominence of universities from relatively small, export-reliant countries, where English is an official language or is widely spoken”, Ellie Bothwell reports. “The ranking is led by two Swiss universities: ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich; and the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne.”

Next in the ranking are the University of Hong Kong and the National University of Singapore. Doesn’t it look funny now that not the most international universities in Finland are trying to attract the world’s most international countries’ students to come and invest their money in not so high-ranking higher education?

“Below the top four is a glut of institutions from the UK, Australia and Canada: prominent destinations for international students and scholars because of their prestigious universities and their use of English, the global lingua franca”, notes Bothwell.

What is wrong with Finnish internationalisation of higher education?

The first thing to consider is national policies for internationalisation, whether they work.

Robin Matross Helms and Laura E. Rumbley of “Inside Higher Ed” criticize the Finnish government’s strategy that mentioned above that had an enrollment goal of 20 000 non-Finnish degree students by 2015. Why do they need so many foreign students? What are they going to do with them? Is this number the only assessment of successful internationalisation?

“When it comes to the more nebulous, longer-term outcomes and impact of such policies, specific data and clear answers about impact are fairly scarce”, Helms and Rumbley argue. “This may be due to the sheer newness of many of the internationalisation policies now in place around the world. In many other cases, evaluation of impact appears not be built in to policy implementation structures.”

They suggest the following measures to ensure the significant impact of internationalisation:

1. Don’t underestimate the importance of government funding,

2. Engage the right players,

3. Avoid undermining one policy with another,

4. Seek synergies between national and institution-level internationalisation policies.

Easier said than done. According to Helms and Rumbley, it requires broad awareness of policies in place and dialogue among national and institutional policymakers. “Ensuring that higher education around the world benefits from the best of what comprehensive, sustained, values-driven internationalisation has to offer will take a great deal of creativity, substantial resources, and sheer hard work. Hard, yes—but, most certainly worthwhile”, they conclude.

In other words, what Finland needs is not numbers-driven internationalisation but values-driven one!

The Era of Academic Capitalism

Another interesting point is made by Hans de Wit of the same publication “Inside Higher Ed”. He says that internationalisation should be much more than student recruitment to generate revenue and calls it academic capitalism. Wit argues that it is “turning universities away from their public purpose, including the public good of internationalisation aimed at enhancing the collective quality of life for communities locally, nationally and globally”.

For Finland it is also turning away from its social values, equal rights for education.

“While the UK and Australia have for more than 40 years had a policy to see international students as a source of revenue, other countries treated them the same as their own students”, he writes. “Only over the past decade can we see other countries moving in the direction of the UK, US and Australia. Canada, The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and recently Finland have started to introduce full cost fees for international students. Germany and Norway are two of the few exceptions among the developed countries.”

In a statement in Pienews, Vicenzo Raimo, Pro-Vice-chancellor of Global Engagement at the University of Reading states that “it’s clear that too often internationalisation within our universities is too narrowly defined as the inward mobility of international students, and then generally only for the economic benefit they bring.”

So, what should be the focus then? I suppose the main idea of internationalisation is to attract the best students and scholars from around the world, launch partnerships with overseas institutions and businesses, incentivise cross-border research collaborations and educate local students to become global citizens.

“The main focus is almost always on the recruitment of international students and (related to this policy) to develop programs in English and increase their position in the international rankings”, notes Hans de Wit. “What contribution they make to the public good by doing so and how it helps their local students to become global citizens remains in doubt.”

It is very unlikely that the economic benefit of internationalisation lies in tuition fees. Karl Dittrich, president of Vereniging van Universiteiten suggests that recent figures show that about 35 per cent of international Master’s and PhD students in the Netherlands remain in the country after graduating, adding €1.6 billion to the Dutch economy each year in tax revenue. “But the most important thing is we have a real international network of alumni; and if these alumni feel they have been trained and educated well, they are all ambassadors for what is going on in the Netherlands,” he says.

The question is whether this focus on revenue generation from elite, rich international students is sustainable. Finland seems to insist on making money on students from outside the EU. How about higher education capacity in the developing world? How about the political and economic instability? How about the limited capacity of families that can afford international education? All these factors make the long-term predictability of this type of revenue generation pretty uncertain.

Finally, coming back to China and marketing Finnish education there: Do you know that recent data from China show already a slowing of the growth in students going abroad?

I think it is high time Finland stopped playing around with internationalisation and started a serious investigation into what, why and how.

Correction 6.3. 2017 14.06: Minor grammatical corrections.